The “Standards for Being a Good Student and Child” (Di Zi Gui, 弟子規) is a traditional Chinese textbook for children that teaches morals and proper etiquette. It was written by Li Yuxiu in the Qing Dynasty, during the reign of Emperor Kang Xi (1661 – 1722). In this series, we present some ancient Chinese stories that exemplify the valuable lessons from the Di Zi Gui. The first chapter of the Di Zi Gui introduces the Chinese concept of xiao (孝), or filial duty to one’s parents.

Filial piety — essentially respect for one’s parents and elders — is the cornerstone of traditional Chinese society. In the first installment, we introduced this concept through the stories of Min Ziqian, whose forbearance changed the heart of his wicked stepmother, and Qi Jiguang, whose father’s admonitions when he was a youth enabled him to become a great general.

One aspect of being filial is to honor one’s ancestors. While ancient Chinese would worship their ancestors at a special temple, and had to follow strict codes governing the proper relationship between older and younger family members, what was most crucial was to maintain one’s character and moral integrity.

Knowing to learn from mistakes

The Di Zi Gui states:

無心非 名為錯

有心非 名為惡

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

An error made by accident

Is called a mistake

An error made on purpose

Is called evil

過能改 歸於無

倘掩飾 增一辜

Mistakes can be corrected

And returned to nothing

But hiding your actions

Adds yet a crime to the deed

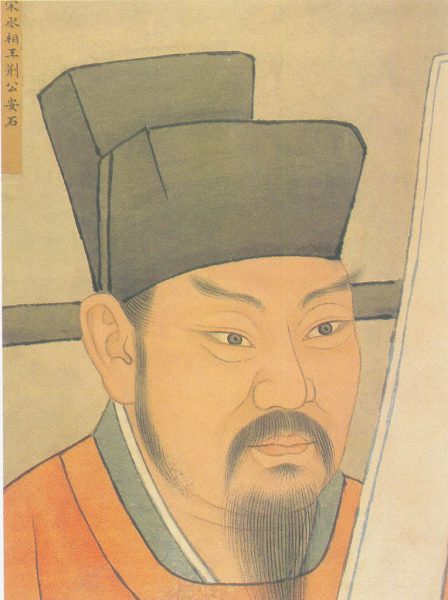

The famous Chinese literary giant, Zeng Gong, had a close friendship with Wang Anshi, prime minister of the Song Dynasty (960–1279). One day, Emperor Shenzong asked Zeng Gong: “What do you think of Anshi’s personality?”

Zeng Gong answered: “Anshi’s writing is as good as that of Yang Xiong in the Han Dynasty. However, because he is stingy, he is not as good as Yang Xiong!”

The emperor said: “Anshi doesn’t care too much about fame and money, so why do you say that he is stingy?”

Zeng Gong replied: “What I mean by ‘stingy’ is that Anshi isn’t willing to correct his mistakes even though he is aggressive and has achievements.” The emperor heard his words and nodded his head to show agreement.

Wang Anshi was famous because of his talents and knowledge. However, he was stubborn and never admitted any wrongdoing. In his insistence on enforcing new and unproven legislation, he eventually brought harm to the people and was left with a bad name in history.

The great sages of China were not people who didn’t make mistakes. Rather, they made mistakes, but they corrected them quickly. They often examined themselves and criticized themselves appropriately.

An emperor tastes his mother’s medicine

The Di Zi Gui states that we should take care of our ill parents, and attend to them day and night without leaving their bedside. When our parents have passed on, we should always remember them with gratitude, and feel sad for not being able to repay them for raising us. We should commemorate our parents’ anniversaries in memorial ceremonies with utmost sincerity, and serve our departed parents as if they were still alive.

親有疾 藥先嘗

晝夜侍 不離床

When a parent is ill

Taste their medicine

Attend to them day and night

Without leaving their bedside

喪盡禮 祭盡誠

侍死者 如事生

Fulfill the funerary rites

Perform the ceremonies sincerely

Serve the dead

As you would serve the living

One such moral paragon is Emperor Wen of the early Han Dynasty, known as the Western Han.

During the Western Han Dynasty, after its founding patriarch Liu Bang died, the throne was passed down to his son, Liu Heng. His posthumous name is Han Wen Di (漢文帝) — “The Learned Emperor of Han.” As a ruler, he practiced rigorous, just governance, and he loved the citizens, moving and inspiring them to self-improvement through education.

At the same time, Emperor Wen did not forget his own family despite having to manage the imperial court. History remembers him for his devotion to his mother, not leaving her bedside as she lay ill.

For three years, after completing his administrative work for the day Liu Heng would immediately leave the state chambers and attend to the empress dowager. He would wait on her day and night, never complaining or expressing displeasure about the toil that others would likely have turned over to a servant.

The emperor’s care was thorough to the last detail. Often Emperor Wen forgot to change his robes for long periods out of fear that he might leave his mother in some discomfort. As soon as the servants had prepared any dose of medicine, the emperor would first sample the remedy himself, to make sure it was neither too hot nor too weak. When it was fit to drink, he would personally spoon-feed her the medicine.

Emperor Wen’s reign was part of the 40-year golden age known as the “Rule of Wen and Jing” (文景之治) spanning two emperors between the years of 180 and 141 B.C. Emperor Wen’s wife, Empress Dou, was a devout believer in Daoism, which stresses the natural order. As a result of her influence, both her husband and her son, Emperor Jing of Han, followed policies of light government regulation and tried to achieve the Daoist ideal of a ruler who leads without the subjects being aware that they are ruled.

As for Emperor Wen, his personal virtue was praised as much as his humane and patient governance. His filial piety became an example for future rulers to follow, and students of history continue to admire his selfless conduct.

Read the next installment here.