It is not uncommon to find a relationship between plants and animals. We are well aware of the role insects play in spreading pollen from plant to plant while they feed on nectar, initiating the development of fruits and seeds.

Yet there are many other ways in which plants and animals work together that may really make you wonder at nature’s perfections in balance and harmony. These living beings from different kingdoms form complex relationships in which they depend on one another to survive; mystifying us simple humans.

Ants and plants

Ants are often found marching in colonies within the barks of trees. What we may not realize is just how close the relationship between these tiny insects and their towering tree may be.

Acacia ants find themselves right at home in the Australian and African native Acacia tree, native to Australia and Africa, and naturalized in South America. The tree’s long, sharp thorns that deter most animals from eating the leaves offer shelter to the ants. Residing inside these thick, hollow thorns, the ants feed on nectar provided by the tree’s flower. In return, the ants will defend their home from herbivores by giving them nasty stings in their mouths.

This relationship turns out to be a bit one-sided however. In studying these ants, researcher Martin Heil discovered that after consuming the nectar of the acacia, they lose their ability to break down the sugars from the nectar on their own, due to an inhibiting enzyme present in the sweet sap. This effectively locks the ants into service, as they can no longer feed on nectar from any other plant.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

In South America, another example of symbiosis between ants and plants can be found in the rainforest, in a ‘garden’ believed to be grown by demons.

According to Stanford graduate student Megan E. Frederickson in the journal Nature, devil’s gardens are areas in the Amazon rainforest consisting almost exclusively of one species of tree called Duroia hirsuta and is believed to be grown by an evil forest spirit in local legend.

A hypothesis explains that the garden is being protected, not by demons, but a species of ant.

The devil’s garden ant is argued to be responsible for the destruction of any plants competing against the Duroia hirsuta trees in which they reside. This ensures conditions for Durioa saplings to thrive, promoting the expansion of the ant colonies.

Studies conducted by Frederickson suggest that the ants will attack any tree or plant, except the Duroia hirsuta trees.

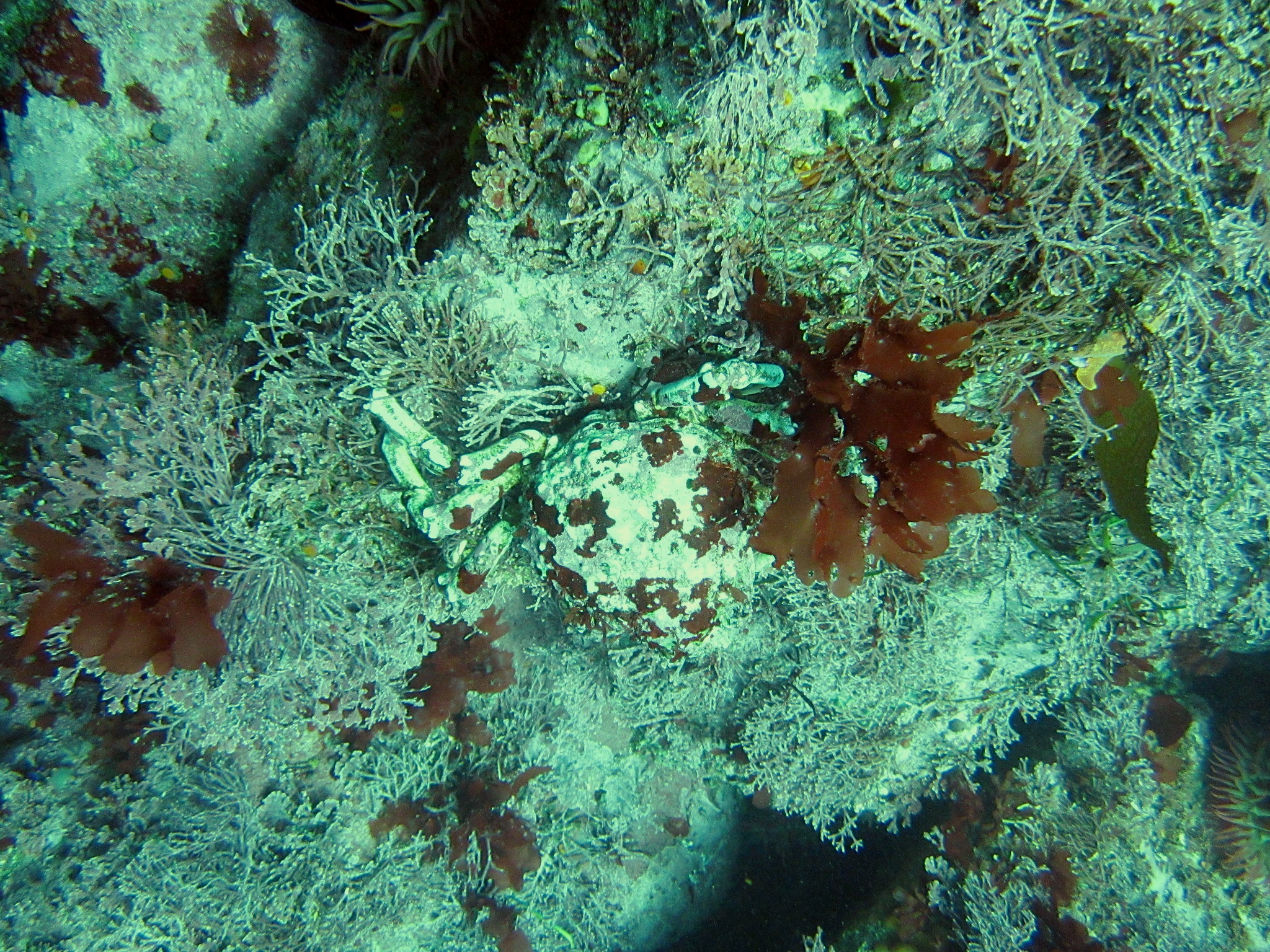

Underwater rider-hider

A hard shell and powerful claws are not enough to protect crabs against the larger predators. As they are generally highly visible prey, some species have found clever ways to camouflage themselves as they scurry across the ocean floor.

Hermit crabs, of course, take an abandoned shell as a mobile home; some crabs cover themselves with other sedentary animals, like sponges, and others blend in almost perfectly with the sand. One species of spider crab takes an active approach to avoiding its predators.

This spider crab covers itself with greenish-brown algae, cut to make its own living camouflage; something akin to a grassy ghillie suit worn by soldiers to hide within thick vegetation.

With this earthy green jacket, the crab becomes invisible to most predators, blending into the colourful world of the ocean floor, and earning it the moniker “decorator crabs.”

While protecting its host, the algae benefit with a lift to other areas of the ocean where they can further colonize, and access to more of the water’s nutrients as they move about.

Scent of dinner

When damaged, some plants release volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which not only deter herbivores, but also attract predators towards their intended targets.

For example, a tobacco plant damaged by a caterpillar will release VOCs that rapidly spread through the air. While the caterpillar is unaware of and unaffected by the signal, predatory insects get the message, and take quick action to hunt down the pest. Broad bean plants attacked by aphids use the same method to attract predators to eliminate the aphids.

By sending out VOCs, the plants gain protection from pests, while offering the predators an easy meal.

Non-insect pollinators

Insects are not the only pollinators out there. About 9% of the world’s mammals and birds are believed to help plants spread their pollen and propagate.

Bats are actually more significant pollinators than one might imagine. They are especially important in warm climates, pollinating succulents with their extra long tongues at night. In addition, a number of plants have nocturnal flowers, which bloom when most insects are inactive. It should come as no surprise that these winged beasts are the principle pollinators of the mammalian class.

While the hummingbird is readily recognized as a pollinator, with its diminutive size and its long beak, several parrot species are also known to pollinate. The swift parrot specializes on the flowers of the Tasmanian blue gem tree, which needs the parrots to disperse pollen throughout their rather isolated environment.

The hanging-parrot pollinates mistletoe, Macrosolen cochinchinensis, whose flowers open only when visited by birds. The plant reacts to a perching bird by quickly opening a nectar rich flower to expose the reproductive receptors while showering the bird with pollen.

Avocados and the super-poopers

Avocados are such a popular and prolific fruit; it’s hard to imagine that they were once believed to be close to extinction. These fatty green fruits had seeds so large that they could only be consumed and defecated whole by megafauna, large animals like mammoths and giant ground sloths that roamed the Earth tens of thousands of years ago.

After the megafauna became extinct, avocados had no animal host to spread the seeds. They sprouted where they dropped, forcing saplings to compete with the parent plant.

Had not humans begun to cultivate these tropical/subtropical evergreens, they might have disappeared altogether. Our selective breeding for more flesh and smaller seeds may enhance their chances of survival even if we were to lose interest in the future.

Reflecting on the complex and ingenious associations that exist among plants and animals may be instrumental in discovering our own strengths and weaknesses; identifying where we need help and where we can give help. Working together to improve as a whole is always more productive than struggling against one another in endless competition.

Ila Bonczek contributed to this report.