The Sámi people of Northern Scandinavia are descendants of centuries-old nomadic peoples who lived off hunting and fishing. In the late twentieth century, the Sámi population consisted of 30,000-40,000 Sámi in Norway, 20,000 in Sweden, 6,000 in Finland, and 2,000 in Russia. Almost all Sámi now are multilingual. The Sámi are known for several unique parenting traditions which help sustain their unusual lifestyle.

Reindeer herding

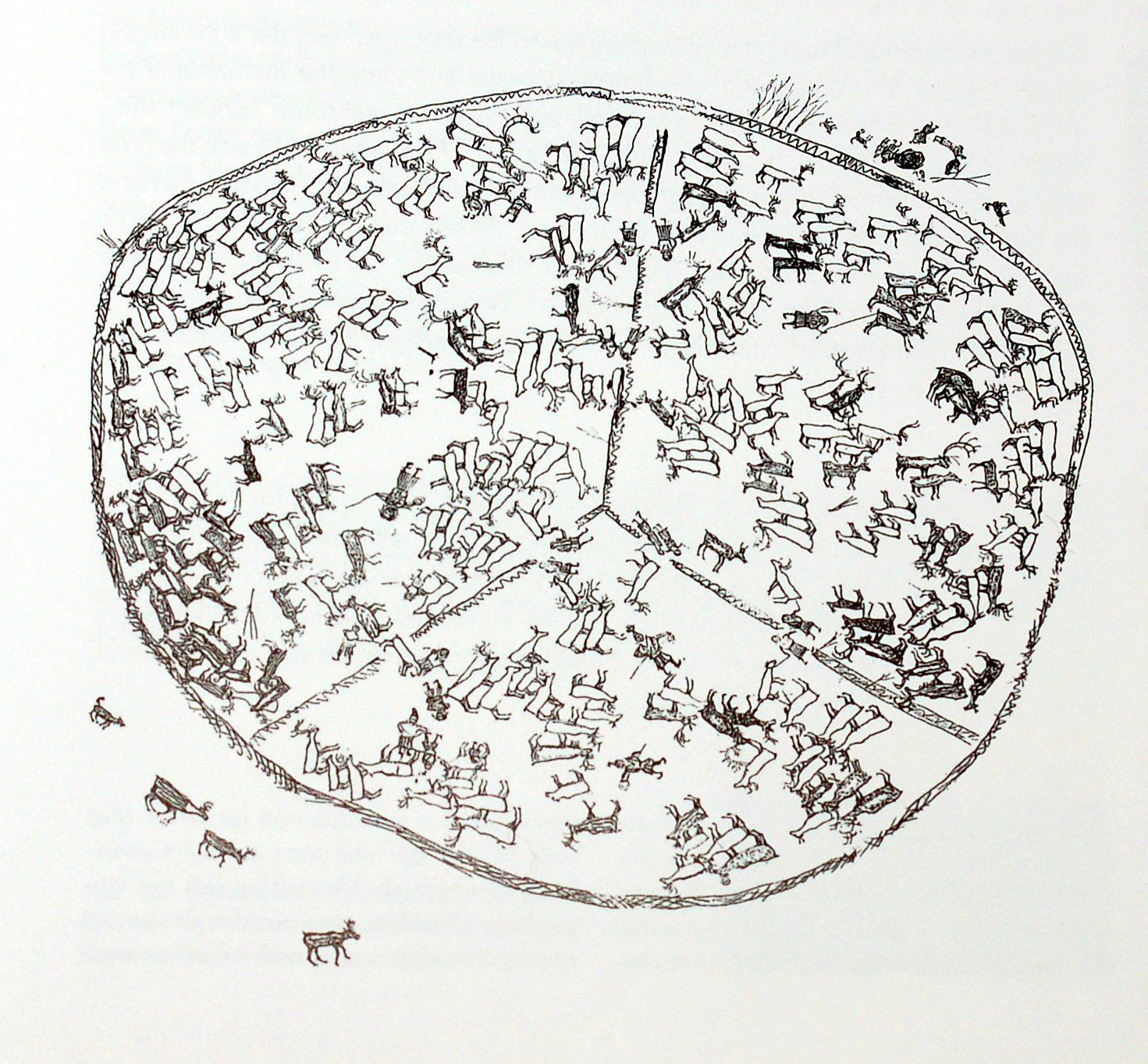

Following ancient customs, Sámi reindeer herders meet in June or July, when daylight lasts deep into the night, to “earmark” their young reindeer calves. The semi-wild reindeer are herded on foot, by ATVs, and even aircraft. Participation is required by all clans. The calves are caught and earmarked with special knives. Each family has a unique earmark pattern used to identify their personal herds. The earmarking procedure is done at night when the temperature is cool, and the task takes weeks to complete.

Cooperation is crucial among Sámis. The entire family reverses sleep cycles. Children work and play with their extended families all night, and then rest whenever they feel like it during the day. Sámi children are raised to be self-reliant and responsible. Even in freezing temperatures, they decide what to wear, eat, and when to sleep. This amount of autonomy may surprise visitors. On summer nights in the Arctic, it’s common for older children to go fishing with pals late at night and return early the next morning.

Unique parenting

The seemingly ruleless Sámi method of raising children has its own intricate structure and philosophical underpinnings. It evolved through time to prepare children for the harsh rigors of Arctic existence.

An expanded network of adults participate in the child’s upbringing. The network provides child care, protection, and communication with persons beyond the nuclear family. Guardianship is a close connection, like kinship. Adults utilize advanced child-rearing techniques like storytelling, playful teasing and distracting strategies and behaviors.

Teaching cultural standards

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

According to a recent BBC article, Rauni Äärelä-Vihriälä, mother and assistant professor of Sámi education at Guovdageaidnu’s Sámi University of Applied Sciences said, “We believe that children must be given time to think and express their opinions, and they also need to fail to learn.” A Northern Sámi expression says “Gal dat oahppá go stuorrola,” meaning “He/she will learn when he/she grows up.”

Sámi teach cultural standards subtly, using indirect, non-confrontational approaches; thereby increasing a child’s self-esteem, improving self-control and promoting levity. One might wait until everyone’s attention is diverted before bringing up a difficult or contentious issue, or use lighthearted teasing, called Nárrideapmi, to remind children how they should behave. Nárrideapmi is frequently performed by aunts and uncles who know the child well, rather than parents.

Rauni said, “For a teenager, it can be something about girlfriends or boyfriends, whereas for smaller children it could relate to dressing up, for instance. If I notice that my child has not worn enough warm winter clothes, I can ask her whether she is going to the tropical beach or something…That also makes the child realize what she needs to do, and it encourages her to think for herself. It is again quite indirect.”

Sámi traditional beliefs challenged

Oral tradition and archeological evidence show that the Sámi people held a deep respect for nature. They believed that the sky was full of spirits and that the landscape’s protruding rocks and abnormalities provided entrance points to the spirit realm. Legends of the Akka (female spirits) and Stallo (clumsy giants of the woods) have been preserved in Sámi folklore and music.

Joiks are a musical art form and have no known origin since the Sámi culture did not have a written language in the past. According to oral tales, the Sámi People received Joiks from the fairies and elves of the polar realms. Joiks mainly consist of chanting. They might characterize someone’s looks or personality. They can also be animal noises. Joiks can be performed for amusement or spiritual purposes. A noaidi (Sámi shaman) might use Joik and a Sámi drum to communicate with the supernatural realm.

Sámi song called Sámi Eatnan Duoddariid, sung by the famous Nils Aslak Valkeapaa

Translated lyrics Sámiland's wide expanses home to Sámi children cold barren rocky realm home of Sámi children Oh, the barren plateau the cold hard area. Northern rocky, snowy world. the home of Sámi children The wind leads, the wind brings, Tundra is tundra. Behind the tundra, in tundras lap, the Sámi embrace of hope. Oh the golden plateaus, their water's silver stars. Precious home of Sámi children, the birth string of life. -Espen Eira-

Sámi culture was almost crushed in the 1600s. Noaidis were burnt as witches and Sámi shamanism was condemned as ‘sorcery. Joiking was deemed wicked and was contentious since it was linked to noaidi and mystical activities.

During the 19th century, the Sámi were increasingly Christianized. With the introduction of compulsory schooling in 1889, the Sámi language and traditional way of life came under increasing cultural strain, particularly between 1900 and 1940 when Norway spent millions to eradicate them; and the German army’s scorched earth policy in 1944-1945 resulted in the destruction of all existing homes and Sámi culture in Finland and northern Norway.

The ancient wisdom of the Sámi

Much of the Sámi cultural lifestyle and customs have been preserved with wisdom and resilience. In the opinion of the Sámi people, success in life has little to do with financial gain or a distinguished job than it does with the ability to adapt and survive in difficult situations. In addition to surviving in nature, one must also be able to interact with a variety of individuals in a variety of settings.

“A Sámi child grows into thinking that people are all different and one must always be inventive. I would say it is very tolerant,” Rauni said.

Laura KallioinenIn, a Sámi teacher and mother of three children raised in Finland’s most northern settlement, thinks it’s odd how her southern neighbors distinguish between family activities. She says, “…people really invest into the ‘quality time’ they spend with their family. I don’t really understand that, for us, it means like going to the forest to pick berries or going ice fishing, normal things.”

To preserve their traditional civilization and culture, the Sámi minority have admirably stood firm in their ongoing fight to keep their ancient traditions and languages alive in Sámi schools, and safeguarding reindeer pastures. The region still possesses hundreds of thousands of reindeer. Although industrial logging has been pushed back from the most important forest areas, there are still threats, such as mining and commercial construction on traditional reindeer land.

The Sámi believe that the only way to restore the balance between people and the environment is to return to traditional wisdom.