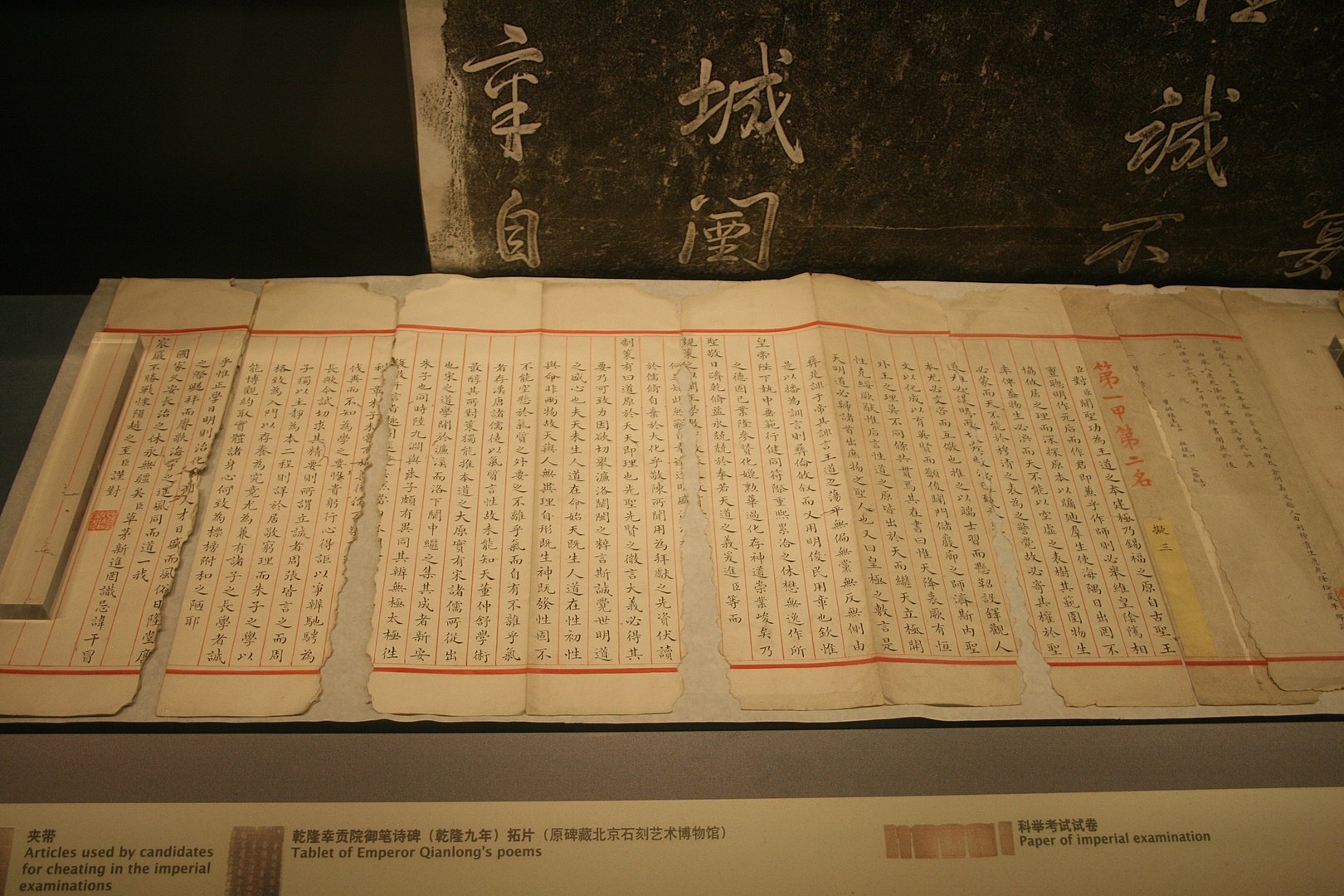

Standardized testing, as we know it today, originated in ancient China. Used as a system to gather the most talented citizens for government positions, the imperial exam was administered every year and tested candidates on their knowledge and ability to lead the nation.

Although this merit-based system has been recognized as one of China’s most notable contributions to the world — bringing stability to the various dynasties that employed it to choose their officials, and later, to foreign countries that adopted it to select potential employees — the current forms of this 1,400-year-old system have met with controversy, especially on educational grounds.

One of the key issues in the debate concerns the effectiveness of standardized tests in measuring students’ abilities and their potential for future success. Other reasons range from the type of knowledge that is assessed to the environment in which the tests are administered.

But why is this examination system, so highly regarded in ancient times, at the brink of being abolished? How has the original system been altered to the point of being considered counterproductive to students’ learning process?

Student’s mindset

Scholarship was one of the noblest aspirations in ancient China. Following the Confucian precepts of propriety, rituals, proper behavior and relationships; men from every social class were motivated to obtain an education.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

Not only was it essential for the moral cultivation of each individual; it also provided equal opportunities to become government officials based on merit rather than birth. This ensured that most Chinese had a basic knowledge of writing, literary classics and, most importantly, codes of conduct.

The imperial exam could be taken countless times and served as a measure of one’s academic progress. The result of these tests was so personally significant to the candidate, that a bad score could easily discourage a fragile soul. This was the case of the late Qing Dynasty (Qīngcháo 清朝) calligrapher Wei Yu, who, in frustration, took to drinking and reckless behavior. Fortunately, he passed the exam once he rectified his conduct.

Those of unwavering spirit took failure in the imperial exam as an incentive to excel. Such was the case of Ni Shan — also known as Zoutian — of the Southern Song Dynasty (Sòngcháo 宋朝), who sat for the exam several times without success but, after each failure, set higher standards for himself and studied ever more diligently until one day he ranked first in the exam.

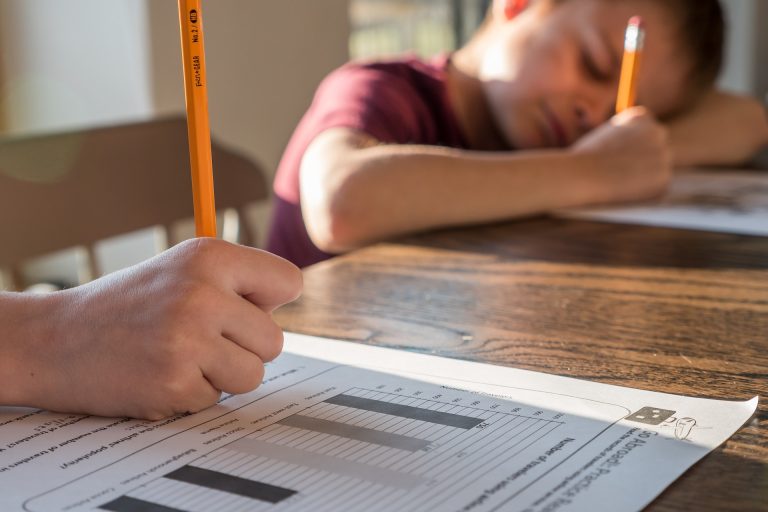

Today, standardized tests are generally used as tools for third parties to assess student progress, rather than an effective tool for students to measure themselves. This is due in part to the withering of academic aspirations in the student’s cultural context, as well as the perception of standardized tests as formalities for advancing along the educational pathway.

The attitude of students towards standardized tests today differs greatly from that in the times of their noble origins. Recent years have seen the emergence of a physiological disorder called “test anxiety,” which refers to the occurrence of extreme stress, anxiety and discomfort before and/or during an exam.

Moreover, the increased propensity of students to cheat on exams, especially with the development of technology, is a clear indicator of declining academic aspirations and, worse yet, declining moral aspirations of students.

Students of the past

The story of Yan Shu, a poet, calligrapher, scholar and court official of the Song Dynasty, can serve as a point of reference to the dramatic change in students’ attitudes. According to historical records, Yan Shu was an unusually talented man who could write poetry at the age of seven. He was introduced to the Emperor Zhenzong of Song (Sòng zhēnzōng 宋真宗), who, upon seeing his talent and potential, granted him exemption from the imperial examination.

Despite receiving such an honor, Yan Shu insisted on taking the exam along with other 3,100 successful candidates. His moral cultivation of self-restraint and patience helped him stay very calm during the exam and answer all the questions well during the first day.

In the second round of the exam, Yan Shu was given exactly the same topic as the first day. When he asked for a new one, the chief examiner advised him to keep the same topic — which he had excelled on the day before — to reduce his chances of failing.

To this Yan Shu replied: “If I pass the examination with the same topic, it would not be done on my true merits. If I fail with a new topic, it means I have to be more diligent in my studies and I will not regret coming to this realization.”

Hearing this, the examiner gave Yan a new topic, on which he wrote an essay that earned him not only one of the highest scores but also respect from others for his honesty and upright character.

Students’ perceptions of standardized tests have indeed changed greatly. Yet students are not the only ones to bear the responsibility for this unfortunate turn of events. In fact, the test itself lost its true essence centuries ago, not because of the subjects it tests but mostly because of the factors it fails to assess.

Criteria of a good student

Our current education system establishes two basic competencies: Numeracy — the ability to understand and apply mathematical concepts, and literacy — the potential to communicate through reading, writing, speaking and listening.

These two foundational skills branch out into more specific subjects spanning from science and statistics to history and geography. Although this curriculum varies from country to country, its foundations are usually the same.

Mathematics was also heavily tested in ancient China. Since statistics and accounting were essential to the management of the nation, candidates of the imperial exam had to master mental calculations, which they referred to as “internal arithmetic,” as well as the ability to use formulas and algorithms, often called “external arithmetic.”

To test the candidates’ ability to communicate coherently and display basic logic, imperial candidates were required to write an eight-part essay with a defined structure. Not only did these essays have to contain a set number of sentences and words in total, but they also had to follow specific rhyming techniques.

Our current curriculum is generally limited to these areas, based on the concept that numeracy and literacy enable students to reach their full potential by developing their critical thinking and creative skills.

However, for the Chinese, these subjects merely tested students’ ability to acquire knowledge and learn skills, and while they were important to the development of the country, they were not the defining measure of how good or capable a candidate was.

Beyond theory and skills

The emperors wanted to make sure that the future servants of the country were not only knowledgeable in arts and sciences, but also virtuous enough to follow the Way of Heaven. According to the ancient Chinese, only by respecting and following the will of Heaven could peace and harmony prevail on Earth.

But what did it mean to be virtuous and how could it be evaluated in the exam? Virtue referred to the moral and spiritual qualities of the candidates. It implied having an upright character, which manifested itself in an individual’s dutifulness, compassion, sincerity and filial piety.

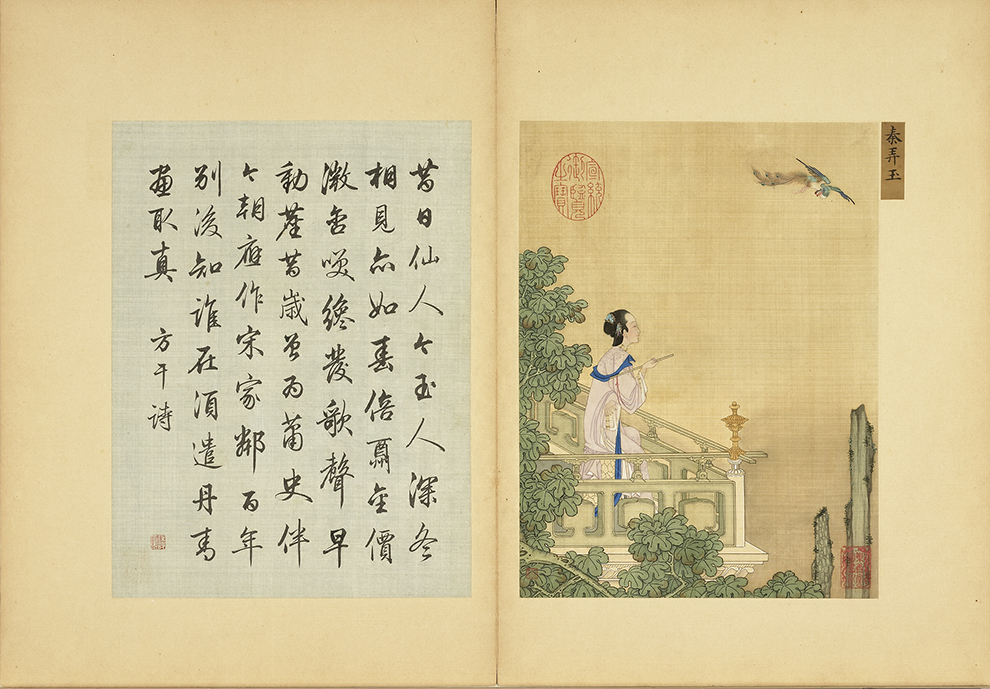

To assess this unquantifiable but essential trait, the Chinese used what they thought to be the window to a person’s soul: poetry. Implemented during the Tang Dynasty, the poetry section of the exam required candidates to write a shi (Shī 詩) poem — classical compositions consisting of 12 lines, each containing five characters, and a fu (Fù 賦) poem — a type of rhymed prose. The themes of these pieces were of a philosophical or spiritual nature to better reflect the applicant’s inner world.

Yet the imperial examination went even further to assess the character of each applicant. Alongside poetry, a person’s calligraphic skill was considered an expression of a person’s self-cultivation. Whether a character’s strokes were painted with grace and attention to detail, or whether the brush struck the paper with careless force, all could be told at first glance. The evaluation of calligraphy provided key information about the calligrapher’s temperament. So… what exactly went wrong?

The very moment when standardized testing focused on theory and cognitive skills to the neglect of students’ character was a turning point not only for education systems, but for society as a whole.

Historically speaking, this change took place with the advent of modern times, when the focus on Confucian teachings and spiritual refinement was criticized, deeming science and technical knowledge as more important for a nation’s progress.

At that time, corruption and foreign invasions progressively weakened the rule of the Qing Dynasty (Qīngcháo 清朝), leading to the abolition of the imperial examination system and, later, to the fall of China’s last orthodox dynasty.

As society continued to value the accumulation of knowledge as the noblest academic pursuit, the cultivation of virtue and character refinement became a personal choice rather than a national aspiration. Without a solid moral fabric in society, the purpose of attending school shifted from becoming a virtuous individual to obtaining the means to make a life for oneself, and academic achievement became a measure for personal growth.

The indifference or negative attitude of some students towards attending school and being assessed, may be due to their inability to identify the purpose of education beyond the possibility of entering the job market. In addition, the underhanded means some of them employ to get ahead in school are the result of society’s failure to encourage the cultivation of their most essential virtues early on.

For those who are fortunate to have a healthy home environment where morality and ethics are deeply valued, resisting the influence of a negative social environment may prove challenging, especially in a society where being traditional is seen as backward, and basic moral discernment is met with pretexts like “anti-discrimination” and “value-neutrality.”

If society returned to traditional educational goals, students would see school as an opportunity to become the best version of themselves. There would no need to worry about cheating, as students would value tests as an opportunity to accurately measure their progress and identify their shortcomings. With a dignified mindset, test takers would not fear failure, but see it as a motivation to become more diligent.

With the cultivation of moral values and noble aspirations from an early age, society would be blessed with upright citizens who foster social stability through self-discipline and good leadership. And while it would take many changes in mindset and method to make this a reality, Chinese wisdom enlightens us once again with powerful advice, “千里之行,始於足下” meaning “The journey of a thousand miles begins with one step.”