An ever-increasing amount of electronic information in our everyday lives is causing us to become hyperstimulated and unable to focus or relax. Monks in the Middle Ages also had a difficult time focusing, and their whole lives were devoted to concentration. We may find some guidance in the path they created to achieve peace of mind for themselves.

Concentration

As the basis for the Medieval monastery, and as an important component of their religious practice, medieval monks were required to engage in concentration exercises. However, many monks reported discontent about not being able to focus. They would daydream or yearn for creature comforts even when studying scripts. A few of them were even worried about being distracted while sleeping or in their dreams, and they would accuse demons of interfering with them.

John Cassian was an ascetic monk, and the founder and first abbot of the renowned monastery of Saint-Victor in Marseille. He was also a theologian at the University of Paris. His teachings, which have had a profound impact on all of Western monasticism, themselves reflect much of the teaching of the Desert Fathers, a group of Egyptian monks who, starting in the 3rd century, practiced austerity in the Egyptian desert, laying the groundwork for Christian monasticism. Cassian rose to prominence as an early exponent of Semi-Pelagianism, which held that salvation was a result of God’s mercy but also dependent on human participation.

Cassian, whose ideas on thinking have inspired generations of monks, was fully aware of the issue and understood that the mind was the source of the problem. It is the most challenging element to manage and seems to be ”driven by random incursions. It wanders around like it were drunk. It would ramble on about its future goals or regrets from the past. It couldn’t even keep its attention on its own amusement – let alone on the challenging concepts that required absolute concentration and deliberation,” he would say.

It was around 420 AD when monastic groups proliferated throughout Europe and the Mediterranean compared with a century earlier, when ascetics generally lived alone. The growing enthusiasm for community work influenced monastery planning. By working the land, baking, or weaving they could enter into a state of concentration much more easily. These creative social settings were believed to operate best when monks were given clear instructions.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

The monk’s duties included concentrating on spiritual communication, reading, praying, and singing. The mind wasn’t meant to be relaxed. It was to be energized and always striving for its goal. Their favorite expression for concentration was from the Latin tenere, which meant “to cling to something.” To do so effectively, the monks or nuns had to overcome their physical and mental flaws and work hard on themselves.

Monastic theorists observed that the mind wanders to recent happenings, and only by letting go of useless habits could one have fewer thoughts fighting for attention. Monks had to learn restraint in all situations and lead a humble life. Specific procedures were put in place to assist the monks in training their minds and halt their irrational fantasies.

Caveat cogitator

By embracing the mind’s capacity to imagine, writers and artists create vivid tales or sculpt fantastic creatures representing the concepts they want to convey. This activity helps improve concentration and meditation abilities.

So if a monk wanted to learn something, he would create a sequence of strange animations in his head. The odder the mnemonic device, the simpler it was to recall when he returned to review them. Reading and thinking were used to build complex mental structures. To better understand the subject they were working with, nuns, monks, preachers, and the people they taught were constantly urged to visualize what they were doing.

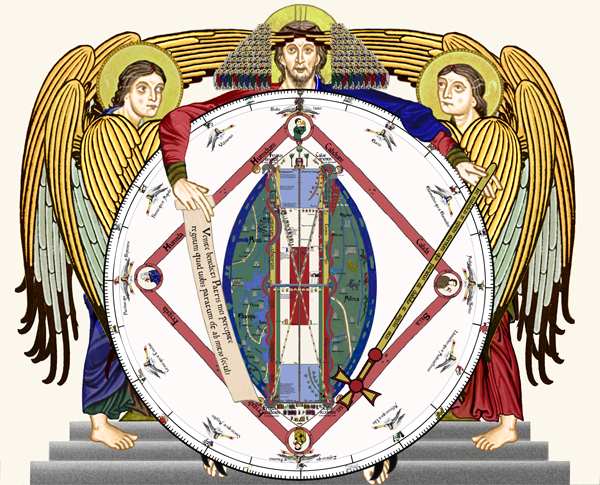

Hugh of St Victor was inspired by a variety of individuals, but most notably by Saint Augustine, who impacted him in his belief that the arts and philosophy may assist theology. The distinguished scholastic theologian established the tradition of mysticism that made the school of Saint-Victor, Paris, a world-renowned institution during the 12th century. Hugh wrote three treatises in 1125–30 structured around Noah’s ark: De Arca Noe morali (Noah’s Moral Ark) on the Moral Interpretation of the Ark of Noah.

The guidebook expounds on the method of visualizing an ark in the heart of the universe. Among Hugh’s imaginative visions was a column rising out of his ark that represented the tree of life in paradise, which, as it ascended, connected the earth and the ark to the generations before it and finally to the vault of the sky. The images serve as organizational placeholders. They represent a text or topic (for example, “Natural Law”) through a tree with eight branches and eight fruits on each branch, representing 64 different ideas grouped into eight larger concepts and were designed to serve as a foundation for advanced theological study.

Its purpose is to provide the mind with something to draw on and satisfy its need for visually pleasing shapes while organizing thoughts into a logical framework.

First-year college students nowadays are sometimes taught medieval cognitive methods. With the students’ ability to construct complex mental apparatuses that provide them with a straightforward method to analyze information; their minds and thoughts are kept engaged by something tangible and captivating, thereby aiding focus and concentration.

Cassian knew that when he offered one of his most basic suggestions – to recite a psalm over and over to keep thoughts under control – the monks would wonder, ‘How are we going to remain focused on that verse?’

Vigilance or watchfulness, as well as other attitudes of concentrated attention on the present moment, is the golden key that constitutes spiritual practice. The philosopher or monk will be able to embody the commitments of their chosen path every minute of their lives if they maintain this level of attentiveness.