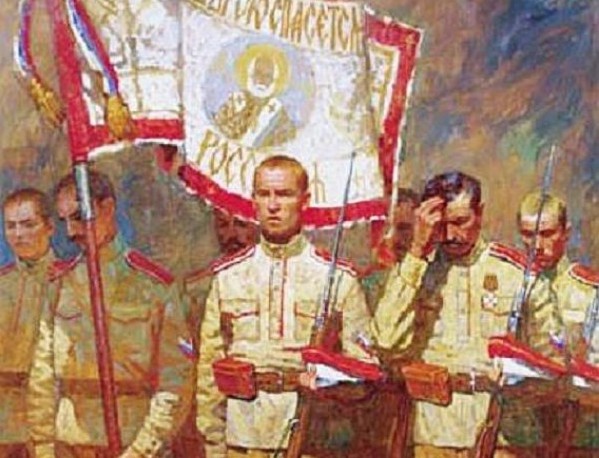

Usurping power and inciting a civil war that killed millions, Soviet communism dominated Russia for almost 70 years, spreading brutal struggle and tyranny around the world. In this series, we feature the leaders of Russia’s ‘White movement’: men who fought — and often paid the ultimate price — in an attempt to defeat the Red Terror. We begin with the main founder of the White Army, Gen. Lavr Kornilov.

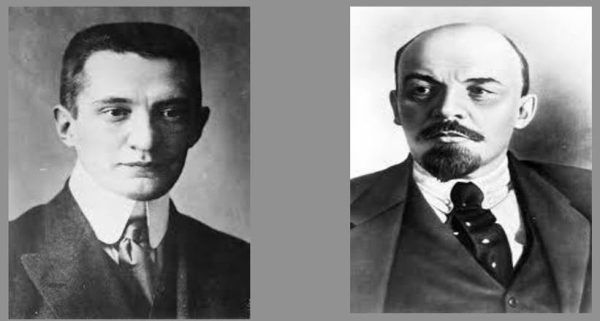

It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that the Russian Civil War was a crucial juncture not only for the nation but for the entire world. The Tsar was toppled and the Bolsheviks under Vladimir Lenin imposed a totalitarian communist regime.

For decades, Russians were educated to look at this tragic historical event through a red-tinted lens as the Soviets attempted to rewrite the past to glorify communism and its leaders.

The officers who led the White movement, which rose up to oppose the Red takeover, were vilified. The sacrifices these heroes made for Russia prior to the revolution were forgotten. Soviet propaganda usually described them as counter-revolutionaries and reactionaries, and denigrated white generals as the chief culprits who started the civil war that engulfed all of the former Russian Empire.

Only after the fall of communism in the 1990s, when memoirs of many “White guards” were published in Russia for the first time, were the citizens finally allowed to see another point of view. Afterwards, the attitude towards the White movement began to change.

The Cossack from Kazakhstan

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

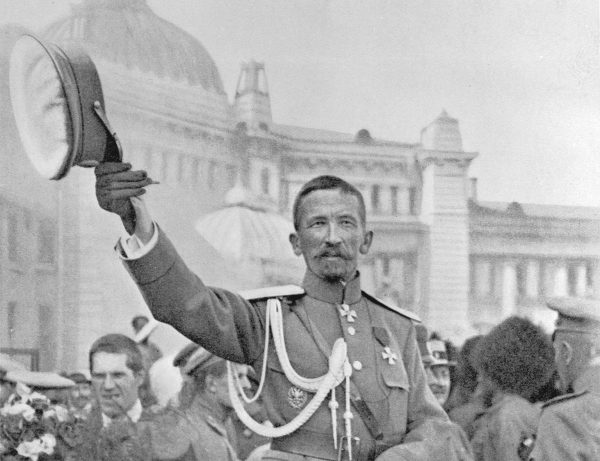

The founding figure of the anti-communist forces was Gen. Lavr Kornilov, a Russian soldier who hailed from the imperial territory of Russian Turkestan. The true biography of this illustrious patriot has little in common with the unflattering depictions of him in Soviet propaganda.

Kornilov was Aug. 18, 1870 in the small provincial town of Ust-Kamenogorsk, in what is now Kazakhstan. His father was an ensign in the Cossack military units, and his mother was Kazakh, from whom he received his Asiatic appearance.

In 1895, Lavr Kornilov graduated from the General Staff Academy with a silver medal and was promoted to the rank of Captain. He had the option to serve in St. Petersburg — the Russian capital — but preferred deployment in the Turkestan military district.

From 1899 to 1904, Captain Kornilov worked in military intelligence. Dressed as a Muslim pilgrim or an Oriental merchant, he traveled to Persia, Afghanistan, India, and Western China to map local resources and roads.

Kornilov wrote several ethnographic and scientific works, such as Narratives About Countries on the Turkestan Borders, Kashgaria or Eastern Turkestan, and Military Reforms in China and Their Significance for Russia.

The 28-year-old officer had already learned eight languages in addition to his native Russian, six of which he spoke fluently: English, French, German, Tatar, Tajik, Persian, and also some local Turkic tongues.

During the Russo-Japanese War, Kornilov fought in battles near Sandepu and Mukden in Northeast China. He was awarded the Order of St. George (4th Class), was promoted to Colonel, and obtained titles equal to those of a hereditary noble.

From 1907 to 1911, Kornilov served as an attaché to China, where he became acquainted with a young Chiang Kai-shek — future president of the Republic of China.

Those who worked with Kornilov noted his quick temper and tough speech, but praised his integrity. Anton Denikin, a fellow leader of the White Movement, described him as a man of few words ill-suited to holding conversations.

From world war to civil war

In 1914, Russia entered World War I against the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary. Kornilov served with distinction as commander of the Russian 48th Infantry Division.

On Nov. 10, 1914, a small group of soldiers from the 148th Regiment under Kornilov defeated two Austrian regiments in the Carpathian mountains, capturing 1,200 prisoners, including one enemy general.

Another Austrian general, after seeing how small the Russian forces were, remarked, “Kornilov isn’t human. He is a force of nature.”

In April 1915, the heroic actions of the 48th Division saved the 3rd Army of the Russian Southwestern Front from defeat. However, in April of 1915 the 48th Division was routed and Kornilov himself was taken prisoner.

For their bravery, all soldiers of the 48th Division were awarded the St. George Cross, while Kornilov was bestowed with the Order of St. George 3rd Class. The General wasn’t aware of his honors and considered captivity a disgrace. Determined to escape, he broke free of his captivity, becoming the only Russian general of the 60 captured during World War I to do so successfully.

But the fortunes of war did not favor Russia, which continually lost ground to the Central Powers and experienced increasing unrest at home. In February 1917, Tsar Nicholas II was compelled to abdicate, leaving a Provisional Government in charge of the former Russian Empire.

But the war continued as Russian leaders were reluctant to abandon the Entente (composed of France, Britain, and other allies) and sign a humiliating peace agreement. Following the February Revolution, Kornilov became commander of the Petrograd Military District (during the war, the German name St. Petersburg was replaced with “Petrograd,” which in Russian means “city of Peter”) and took part in the June 1917 offensive aimed at throwing back the German and Austro-Hungarian armies.

Initially, the assault had moderate success and the German army was forced to transfer some troops from the Western Front to Russia. But eventually, the offensive failed because of poor discipline and low morale among the Russian ranks.

Stabbed in the back

Communist activists exploited the deterioration of Russian morale to further undermine the war effort and spread their ideology during the summer 1917 offensive.

As a result of the February Revolution, a council, called “Soviet” in Russian, was set up in Petrograd to represent soldiers and workers. As the Russian Army fought to turn the tide on the frontlines, the communist-influenced Petrograd Soviet issued its Order No. 1 equalizing the rights of soldiers and officers.

Per the order, soldiers had the option to question any officer’s command, allowing numerous Bolshevik agitators to spread defeatist propaganda among the troops.

The front under Kornilov’s command became the only successful one in an otherwise failed offensive. In recognition of this achievement, Alexander Kerensky, Minister Chairman of the Provisional Government, appointed Kornilov Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Army.

Kornilov was able to achieve his successes on the battlefield in large part due to his insistence on strict discipline. For example, he was able to convince the Provisional Government to reintroduce the death penalty for front-line soldiers who committed crimes or deserted.

In July, the Bolshevik Party organized a revolt which was suppressed by the Provisional Government. Several Bolshevik leaders, including Leon Trotsky, were arrested. Vladimir Lenin, the future leader of Soviet Russia, fled the country.

The mystery of the ‘Kornilov Affair’

Kornilov proposed a program on how to restore discipline throughout the Russian Army and restore much-needed political order in the country. Initially, Alexander Kerensky agreed with the General and in late August requested that Kornilov move forces loyal to the Provisional Government to Petrograd.

But on Sept. 10, Kerensky suddenly dismissed Kornilov from his command. Kornilov refused, and as a result he was named a rebel and arrested following a confusing series of events in Petrograd involving the Russian army and officials of the Provisional Governments. Several generals, including Denikin supported Kornilov, but most of his peers maintained their neutrality during the controversy.

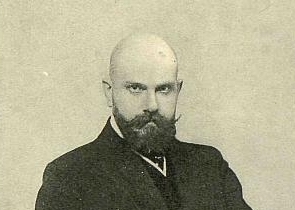

What became known as the “Kornilov Affair” still is a matter of debate because many details remain unclear. Some Russian historians note the negative role played by Vladimir Lvov, Ober Procurator of the Most Holy Synod, a political position established in the 18th century to manage the Russian Orthodox Church.

Despite the Synod’s religious nature, Lvov himself supported the communists. In the early 1920s, he joined the League of Militant Atheists, wrote articles denying the existence of God, and praised communist government. Later, however, he would be arrested by the Soviet regime in 1927 and ultimately die behind bars.

While Kornilov’s proposed military reforms were motivated by the urgent need to enforce discipline so as to save the army and achieve victory, Lvov reportedly convinced Kerensky that the General was in fact plotting a coup to install himself as military dictator. Lvov’s deceit is likely the main reason behind Kerensky’s sudden decision to fire Kornilov and declare him a rebel.

The Kornilov Affair eroded trust between Russian generals and the Provisional Government. In November, when Lenin’s Bolsheviks overran the Winter Palace which housed the Kerensky administration, the Russian army did nothing to defend it.

After the October Revolution , (Russia at the time used the old Julian calendar, making Nov. 7, the date of the Bolshevik takeover, Oct. 25 per the Julian reckoning), Lenin overthrew the newly elected Constituent Assembly after the Socialist Revolutionaries, rather than the Bolsheviks, won the vote.

Reds versus Whites

The Bolsheviks’ seizure of power was by no means accepted across Russia. Kerensky and the Provisional Government may have fallen quickly, but to subjugate the rest of the country and its people would take nothing less than a full-scale civil war and millions of deaths.

In the Don, Kuban, and Siberian regions, Bolshevik popularity was extremely low. In some cities, the Bolsheviks gained even less votes than the Constitutional Democratic Party (Kadets), which garnered just 5 percent of the overall vote. Consequently, these regions became fertile ground for the anti-Bolshevik forces.

As Lenin overthrew the Provisional Government, Kornilov, Denikin, and other generals fled their prison at Bykhov Fortress. They would form the core of the anti-communist movement in the Russian Civil War — the White armies.

In January 1918, the White Volunteer army had just 3,700 personnel, 2,350 of whom were officers. The Don Cossacks, who were tired of war initially, refused to join. They hoped that supporting the new government would allow them to maintain their privileges.

They didn’t know yet that from the Bolsheviks’ standpoint, the Cossacks’ freedom-loving lifestyle and tradition of keeping state authority at arm’s length were incompatible with the plans of the communist regime.

Apart from the Cossacks, Kornilov and other Whites faced challenges in trying to win over conservative officers and generals. Many of them were defenders of the deposed monarchy, and viewed Kornilov, whose career benefited from the February Revolution, as something of a traitor. It didn’t help that he lacked noble heritage and hadn’t enjoyed much prestige in the pre-revolutionary military establishment.

It was also Kornilov who, acting on orders of the Provisional Government, had put Tsarina Alexandra — the Russian empress — under house arrest, while an investigation into the activities of the former imperial family was carried out. Eventually, the government came to the conclusion that Nikolai II and Alexandra were not guilty of any crime.

As the Bolsheviks took power, Gen. Kornilov and the White Volunteer Army, also known as the White Guards, made their base in the southern region of Kuban, home to the Cossacks. Novocherkassk, the seat of the Don Cossacks, hosted the White headquarters.

The ‘Ice March’ and the making of a movement

In the final days of 1917, the Don Cossacks grew convinced of the need to stand up against the Bolshevik regime lest their own independence be imperiled. With their support, the White Guards took the major city of Rostov-on-Don, driving out the Reds with a force of just 500 men.

However, the better-organized and numerically far superior Red Army would soon be back. They would deploy 50,000 to 60,000 men versus Kornilov’s volunteers, which, despite gradually growing in numbers, still counted only a few thousand men.

Because of the trials that the Whites would endure in their debut against the Bolsheviks, the first Kuban campaign became known as the “Ice March.”

From the outset, Kornilov ordered that no military decorations would be given in the White Army, because such awards would be inappropriate in a fratricidal war (later White Russian leaders like Denikin would nevertheless issue a number of medals).

By mid-March 1918, the White Army was 6,000-strong. On March 28, Kornilov led his men in an assault on Ekaterinodar (modern-day Krasnodar), over a hundred miles south of Rostov.

The Whites initially seized the suburbs of Ekaterinodar, and prepared to storm the city despite facing a defending Red Army force three times their size. Kornilov believed in victory, but the assault did not go to plan. On March 31, the General was fatally wounded, and the Whites began to retreat.

To diminish the chances that Kornilov’s remains would be recognized and desecrated, White officers buried the General in flattened garb. But when the Bolsheviks arrived, they recognized Kornilov by his General’s uniform and outraged the body before transporting it back to Ekaterinodar.

There, they tried to hang the dead Kornilov, but the rope broke off and the body fell. A hysterical crowd chopped his body to pieces before burning it.

The Ice March — a strategic retreat and regrouping of the White forces — continued until May. Though the Whites failed in their aim of taking Ekaterinodar and lost their leader, it was a decisive and symbolic moment that rallied the anti-Bolshevik cause.

After Kornilov’s last stand, generals like Anton Denikin, Pyotr Wrangel, and Alexander Kolchak would lead larger armies against the Red Terror sweeping across the territory of the former Russian Empire.

The White officers were a diverse and sadly fragmented force, which contributed to their ultimate downfall at the hands of the Soviets. Some wished for a Russian republic, while others — like those who condemned Kornilov for his actions during the February Revolution — wanted a return of the Tsar. But the Whites were united in their common goal of resistance towards communist tyranny and atheism. They also agreed in principle that Russia’s future form of government ought to be decided by a referendum, held fairly unlike the Constituent Assembly that the Bolsheviks abolished when the result was not to their liking.

The Reds’ brutality in southern Russia caused revolts against the rule of Lenin and the Bolsheviks. A growing number of Cossacks woke up to the communist threat and offered their services to the White Army; they were often joined by ethnic minorities of the Caucasus mountains, such as the Circassians and Ossetians.

Denikin, who took command after Kornilov’s death, noted that the Caucasian peoples had difficulty understanding the politics of the Russian Civil War, as the very concept of “revolution” was alien to them. However, once the Bolsheviks barged into their villages and destroyed their mosques and temples, it was clear that there could be no peace until the “evil bandits” were driven out.